The Hardest Part of Writing a Picture Book

It’s June which means . . . I have a picture book coming out this month! Like every book, it had its challenges. Here's a few of them.

Oh, hey, hello! I hope you’re doing well.

It’s June which means . . . I have a picture book coming out this month!

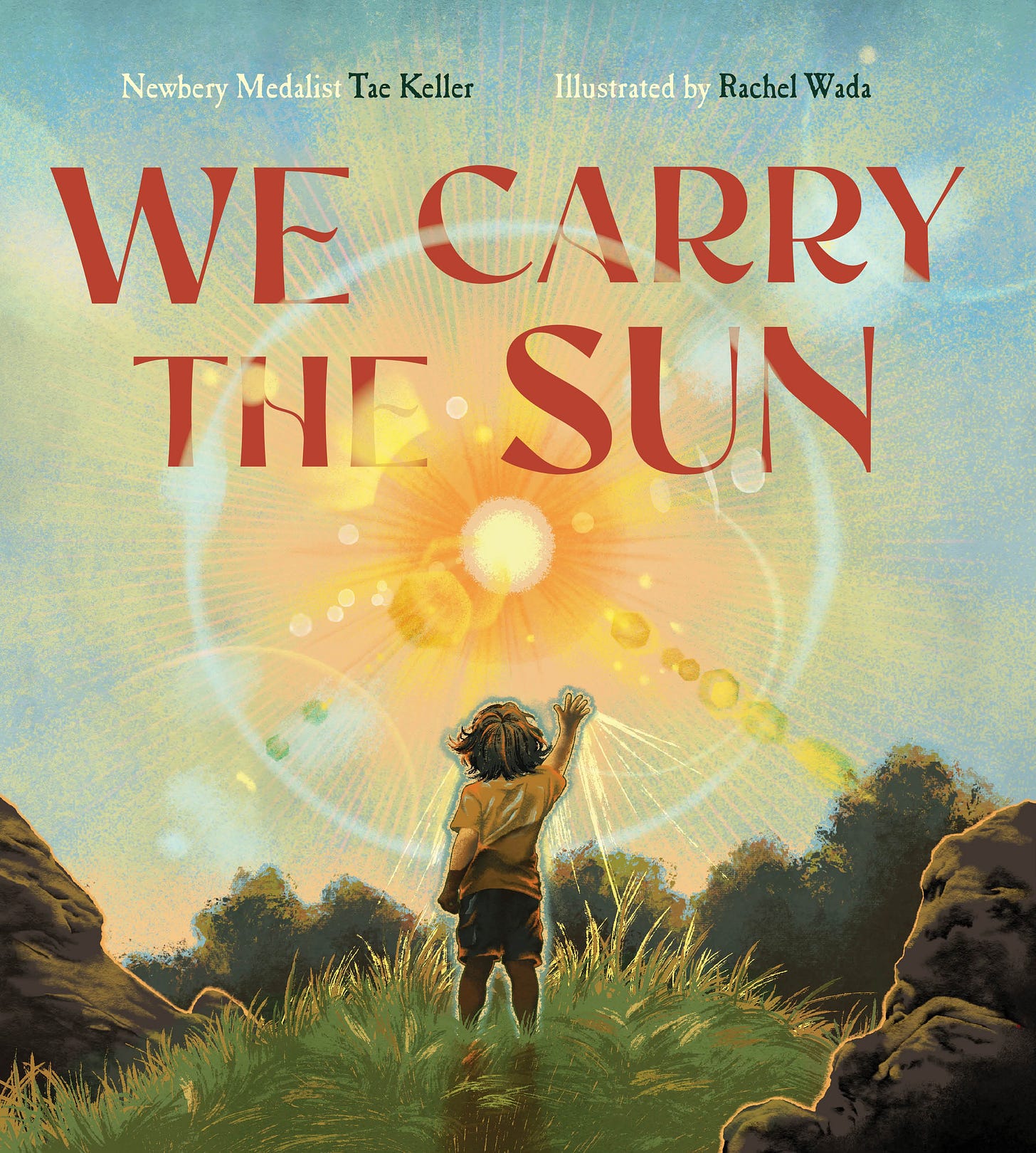

We Carry the Sun is my first ever picture book, and I’m really proud of it. It’s about humans and their relationship with the sun — an epic story spanning from ancient home building techniques to cutting-edge solar panel technology. It’s a story about curiosity and progress and hope, and how we can all be part of a better future.

As for the illustrations, they are absolutely stunning. Rachel Wada is an artist I’ve admired for many years, and I feel very lucky to have her art in this book.

If you’re in the Seattle area, I will be celebrating the book launch on Wednesday, June 18th at 6 pm at Third Place Books Ravenna. I’d love to see you there!

And if you aren’t able to come but would still like a signed copy, order from Third Place Books and put your personalization request in the order notes. ☀️

The Top 3 Challenges of Writing This Book

Every book is challenging in its own way, but because picture books are new for me, some of the challenges were, too.

I thought I’d share some of the biggest hurdles here—

1. It couldn’t be a biography

When I first conceived of this book, I thought it would be a picture book biography. It’s an established niche. It’s accessible. It makes sense.

My friends’ son had become obsessed with solar panels, and when his curiosity sparked my own, I thought, ah, perfect! I shall write a picture book biography of the person who invented solar panels!

Biography writing comes with its own set of challenges, but I’d written one about Patsy Mink for the She Persisted series, so I figured this would be straightforward. I wasn’t foolish enough to utter the famous last words—this will be easy—but I did kind of think them.

Of course, the act of writing humbled me immediately, as it tends to do.

I realized quickly that there wasn’t a single inventor of solar panels. And for that matter—what “counted” as a solar panel? The technology had developed so much over time, where did I draw the line? Where did the story start?

Well, to tell the story of humans and the sun in the most interesting and honest way, I decided the answer to that question would be . . . six thousand years ago.

Decidedly not a “biography” time frame.

So instead, I started to think of the book as an epic poem for kids. Which was exciting! But also meant I was in unfamiliar territory. And on top that . . .

2. Writing was like an act of translation

Deciding to include six thousand years of history and technical scientific developments meant I had . . . a fair amount of research to do.

I spent six weeks gathering sources, reading about each development, and parsing academic articles about modern solar panels. In particular, I worked to find women and people outside the Western world who contributed to these developments, because they are so often left out of “progress” stories.

Then, once I’d collected all this research, the real work began: I had mountains of information, but I had to make that information accessible to kid readers, in a limited word count.

This started to feel like an act of translation. How could I take all this dense history and science and make it picture book appropriate?

The process included some trial and error, but I began to find entry points for kids.

For instance, Augustin Mouchot was a French inventor and engineer in the late 1800s, but before that he was a math teacher. So that became a relatable way to introduce him to readers—A math teacher in France wonders . . .

I searched for fun and familiarity everywhere I could in my research, pulling out exciting and kid friendly moments and images—a mom giving her baby a bath, a brand new invention displayed at an ostrich farm, solar panels powering a space ship.

But then, how to describe a scientific concept like photons? Especially when I was reading articles that included terms that I didn’t even understand, like wave-particle duality and thermal equilibrium and photoelectric effect?

I figured that distilled, into the most basic explanation, this was about energy, specifically an abundance of energy—which is something kids certainly understand. Could I make photons relatable?

But how does this work?

Photons—

tiny particles of light—

bounce around, full of energy,

vibrating strongly enough to create electricity.

Translating like this was challenging, but it was fun and rewarding. And in the end, the hardest part wasn’t translating the science, or choosing which people and moments to select. The hardest part was figuring out how to tackle the climate crisis.

Which brings me to . . .

3. Writing about the climate crisis for kids is tricky

Fossil fuels and pollution are unavoidable in the story of solar energy. Not only are the destructive consequences key to why solar energy is so important, but the profits involved in fossil fuels are also the reason why solar research went dark (forgive the pun) for a period of time.

Right on the verge of some major clean energy breakthroughs, the US slashed funding for it. And the negative impact of that continues to this day. I wanted to be honest about that reality.

But in addition to being honest, I wanted this book to be uplifting and hopeful.

The tricky thing is, I think a lot of “hopeful” messaging around climate often boils down to telling kids that they can solve all these problems.

I understand the impulse. It is empowering, in a sense, for kids to see themselves as part of the solution—and I wanted to capture that feeling of empowerment in the text.

But. I also didn’t want to put the literal weight of the world on their shoulders. This isn’t their problem to solve, all by themselves.

Empowerment comes, I think, from excitement and curiosity, rather than fear and obligation.

It took many drafts to get this balance right.

First, I made sure to highlight all the adults working to make a better world for kids present and future. I wanted readers to know just how many people across the globe are working to take care of them.

And then, after all that ground work, I introduced hte idea that readers, too, could contribute to the solution—that they could be part of something bigger.

I rewrote and rewrote, searching for the right tone, and in the end, I think the biggest difference came from changing a single word.

This is the text on the last spread:

How does an idea grow?

With people bouncing off one another like photons,

teaching and inspiring,

listening and learning.

Across the world,

we turn to one another and say,

We are incredible.

Look at all we can do.

We reached into the sky

and carried the sun home—

And, originally, I had finished that stanza with:

But what if we could do even more?

That felt almost right . . . but not quite.

I couldn’t figure it out. I kept rewriting and rearranging and leaving my desk for days and coming back, trying to figure out what I was missing.

It wasn’t until a week later, in the middle of a long dog walk, that I finally realized:

And.

I rushed home to replace the “but” with an “and” and suddenly the final lines felt right. They felt optimistic and hopeful, and I knew I was finally done.

And—not a negation, but a continuation. An invitation. A promise of what’s to come —

We reached into the sky

and carried the sun home—

and what if we can do even more.

That’s all from me for now. I’ll be sending out a quick email in a couple weeks for pub day.

In the meantime, take care of yourselves, do what you can, and have a sunny June.

With care, as always,

Tae

Reviews for We Carry the Sun

⭐️ “Full-bleed illustrations, both informative (such as the depiction of the first solar home) and bold (as shown in the extraction of oil), enhance Keller’s compelling, poetic text.”

—Horn Book, starred review

“Ideas of collective imagination and community resilience are threaded throughout the text, purposefully including non-European scientific endeavors and extending to climate activists in current day . . . Readers of any age will be caught up in Wada’s truly breathtaking art, every spread a blaze of light-evoking color as curved refractions and radiating rays demand viewers’ attention . . . Pointed and inclusive, this will be galvanizing for kids beginning to understand the full range of powers (scientific and political) in the world around them.”

—The Bulletin of the Center for Children’s Books

“The text is engaging, and the imaginative, colorful, and often dramatic artwork will draw readers.”

—Booklist

“Pages highlight innovators harnessing the sun’s energy across time—a teacher using a solar mirror to power a steam engine, a parent warming her baby’s bath in the sun, and more, each person advancing the science one step further... More than a resource about the history of solar energy, it’s also a look at stepwise progress made by standing on the shoulders of those who have come before.”

—Publishers Weekly

Newbery Medalist Tae Keller’s debut picture book is a resplendent account of humankind’s relationship with our most precious resource: the sun.

From the first human settlements to today’s modern metropolises, we have always relied on the sun for light, energy, and sustenance. We Carry the Sun traces the history of solar power from ancient south-facing villages to the Industrial Age and modern innovators; and from solar-powered steam engines to silicon solar panels.

Lyrical and informed, Newbery Medal winner Tae Keller’s debut picture book is also a timely call to action that asks young readers to imagine a brighter, cleaner future. Illuminated by Rachel Wada’s radiant, eye-catching illustrations, We Carry the Sun is a tribute to pioneering thinkers, a celebration of humankind’s relationships with the natural world, and a shimmering ode to the resource that sustains us.

This looks like such a gorgeous book. Thank you for sharing these behind the scenes!!

This is exciting (and humbling)! The last line is beautiful and perfect. Congratulations!